- BY Kevin Barry BSc(Hons) MRICS

- POSTED IN Latest News

- WITH 0 COMMENTS

- PERMALINK

- STANDARD POST TYPE

Pathways to the Future: When Institutions Must Adapt or Communities Pay the Price

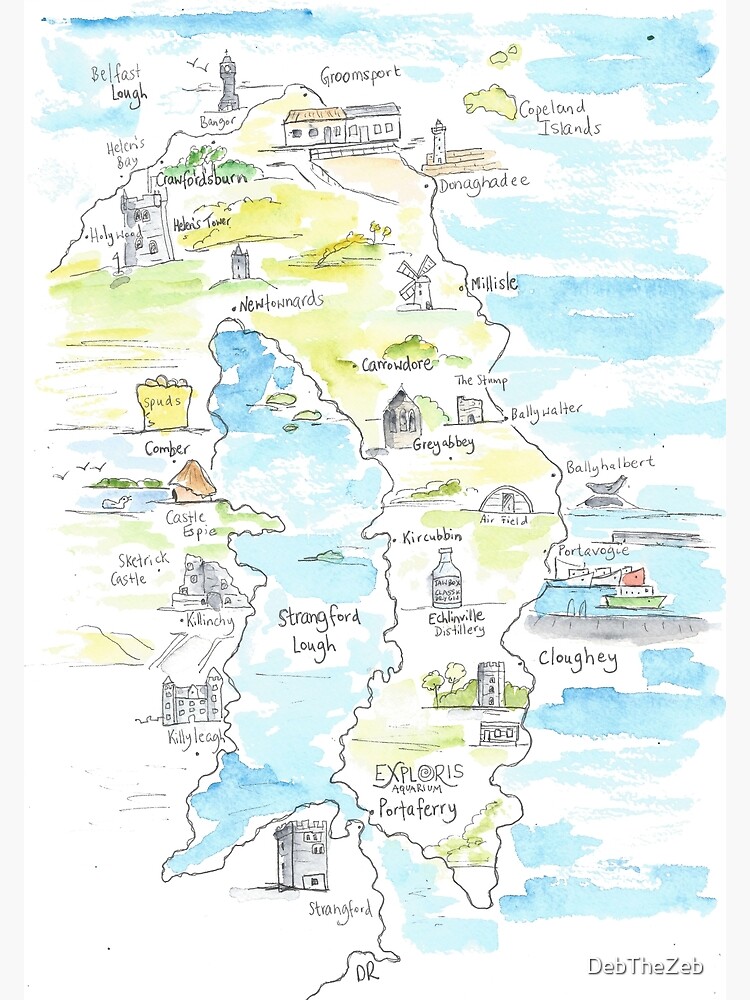

Strangford Lough Crossing Campaign www.strangfordloughcrossing.org

A recent article in The Irish News featured Fr Eugene O’Hagan, one of the celebrated singing trio The Priests, reflecting on the future of parish life in the Down and Connor Diocese. His observations, candid and unvarnished, carry a resonance that extends well beyond church matters. They speak to a fundamental question facing institutions across Ireland: when the world around you has changed, do you adapt, or do you cling to structures that no longer serve the people who depend on them?

Fr Eugene acknowledged that the days of full chapels are over, and that their return is not a realistic prospect. He described it as a desire and a hope, but not one grounded in the realities of the world we now inhabit. He spoke of the increasing demands placed upon a shrinking number of priests, of responsibilities necessarily passing to lay parishioners, and of the need for a fresh approach. His own role within the Diocese’s Pathways to the Future office reflects that imperative: the institution recognises it must change course or risk irrelevance.

This is not merely a story about religion. It is a story about institutional honesty, about the courage to confront uncomfortable truths, and about what happens to communities when those responsible for their wellbeing fail to act.

No One Shouted Stop — Until Now

The parallels with the GAA’s landmark December 2025 report, No One Shouted Stop — Until Now: The GAA’s Response to Ireland’s Demographic Shift, are striking. That report, produced by the National Demographics Committee under Chair Benny Hurl and published by the Gaelic Athletic Association, documents how urbanisation, eastward migration, and rural depopulation are reshaping communities across the island of Ireland with unprecedented speed. The report notes that the population of the island now exceeds 7 million — the highest since 1851 — yet growth is concentrated in Dublin and the commuter belts, whilst rural populations continue to shrink.

The GAA’s executive summary states plainly that these are not distant trends but lived realities, eroding the social fabric of communities. It warns that without urgent, coordinated action, rural clubs will disappear, leaving parishes without representation. Previous reports — the MacNamee Report of 1971 and the Strategic Review of 2002 — each identified the same threats. The warnings were not acted upon. Now, as the GAA itself acknowledges, inertia is not an option.

The Strangford Lough Crossing campaign recognises this same pattern in the Department for Infrastructure’s approach to connectivity on the Ards Peninsula.

The Institutional Parallel

Fr Eugene spoke of a world in which clergy once held an elevated status that is now rightly gone, and of the unhealthy clericalism that such deference enabled. He welcomed its passing and the freshness that change brings. There is an institutional lesson here for the Department for Infrastructure, which continues to refuse even a feasibility study into a permanent crossing of Strangford Lough, despite 94% of 458 surveyed residents indicating that the current ferry service is not fit for purpose (SLC Community Survey, 6th November 2024).

Freedom of Information requests have revealed that the Department’s own cost estimates are self-described “guesstimates” (DOF-2024-0440, Annex B). The same officials who operate the ferry service are responsible for evaluating whether a bridge or tunnel should replace it — a conflict of interest that would not be tolerated in any other sphere of public life. Meanwhile, the ferry operates at just 34% of its maximum capacity (DfI 2023/24 operational data), requiring £3.52 million in annual operating costs against income of only £1.43 million — a cost recovery rate of just 41%.

When Fr Eugene speaks of knowing your strengths and knowing your limitations, he captures something essential. The Department for Infrastructure’s limitation is that it has predetermined its conclusions. Its strength — the engineering expertise and public resources at its disposal — remains entirely untapped. No feasibility study has been commissioned. No independent assessment has been conducted. The position, as stated in DfI correspondence (TOF-0128-2025, dated 9th April 2025), is simply that “the Department’s position has not changed.”

Communities Left Isolated

The human cost of institutional inertia is documented not only in our community survey but in the Northern Ireland Assembly itself. On 3rd February 2026, an Adjournment Debate on the impact of storms on the A20 Portaferry Road brought cross-party contributions that laid bare the vulnerability of peninsula communities.

Kellie Armstrong MLA (Alliance), who secured the debate, stated that the A20 is a lifeline for the Ards Peninsula, with thousands of commuters, schoolchildren, carers and local businesses relying on it daily. She described how, during Storm Bram, a school bus travelling along the A20 was engulfed by waves, and stated plainly that children being stranded by coastal flooding should never have happened.

Michelle McIlveen MLA (DUP) noted that a bridge would provide an alternative route off the peninsula that does not depend on a coast-hugging road vulnerable to storm surge. She stated that it would improve traffic flow for local residents, visitors and emergency services, and would take the pressure off the A20 when that road is closed or unsafe.

Matthew O’Toole MLA (SDLP) observed that storm disruption that disrupts the A20 might often disrupt the ferry crossing from Portaferry to Strangford, which puts even more emphasis on building in resilience for peninsula residents.

Harry Harvey MLA (DUP) described the Department as all too often tone deaf when it comes to the dangers presented by the Portaferry Road.

Mike Nesbitt MLA (UUP) noted the road’s history as a notorious accident black spot that has sadly claimed many lives.

These are not party-political observations. They represent a cross-community consensus, from Alliance, DUP, SDLP, and UUP, that the current arrangements are failing the people of the Ards Peninsula.

Social Connection and Community Wellbeing

The Pivotal Public Policy Forum’s May 2025 report, Achieving Greater Integration in Northern Ireland: Young People’s Voices, found that young people in rural areas emphasised the lack of good public transport as a barrier to socialising or working outside their community. Fear was the most common emotion expressed by young people regarding their wider area, with many reporting feeling unsafe and highlighting the lack of communal spaces. The report’s conclusion is direct: the housing crisis, creaking infrastructure, demographic change, and pressures on school budgets highlight the need to reimagine and rebuild many aspects of public services and communities.

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has documented how social isolation — exacerbated by poor connectivity and rural remoteness — increases risk for heart disease, stroke, diabetes, dementia, and substance abuse (Social Connection and Worker Well-being, CDC Blogs). These are not abstract concerns for the residents of the Ards Peninsula, where the ferry ceases operation at 22:30 each evening and does not resume until 07:45 the following morning. During those hours, the only route to hospital is a journey of over 75 kilometres, or travel to the Ulster Hospital in Dundonald, made more difficult if storms cause diversions onto poorer side roads.

The Cleddau Precedent

Institutional reluctance to change is rarely vindicated by history. When the Cleddau Bridge replaced the ferry crossing (approx 250,000 vehicles per annum) in Pembrokeshire, Wales, in 1975, the end of year 1 initial traffic stood at 885,900 crossings. Like uncoiling a spring, this is termed latent demand. In their case, major oil refineries and support industries had developed over the following years at Milford Haven and by 2024, that figure had grown to 4,745,000 — a factor of more than 20 times the ferry baseline. The MV Portaferry, the vessel which operated the Strangford crossing until 2000, originated from that very Welsh service, transferred to Northern Ireland precisely because Wales had the foresight to build a permanent crossing. Latent demand shall be natural and progress as travellers become accustomed to the new crossing point. It’s growth thereafter shall be determined by the economic policies implemented by the respective councils (Ards and North Down Borough Council + Newry, Mourne and Down District Council) and the NI Executive, to aid regeneration and employment etc.

The HITRANS Corran Fixed Link Study in Scotland — examining a remarkably similar situation of a short ferry crossing serving remote communities — identified social isolation, poverty, an ageing population, and resilience as central considerations that justified permanent infrastructure investment.

The Way Forward

Fr Eugene O’Hagan’s Pathways to the Future work within the Down and Connor Diocese is premised on a simple but powerful principle: identify reality as it is, not as you wish it to be, and build a pathway to something better. The GAA’s No One Shouted Stop report carries the same message with even greater urgency: demographic change is not a future threat; it is a present reality.

For the Strangford Lough Crossing campaign, the way forward requires three specific actions.

First, the commissioning of an independent feasibility study — not by the Department for Infrastructure, which has demonstrated an inability to approach the question objectively, but through an independent process potentially funded via Ireland’s Shared Island Fund or through the UK Government’s National Wealth Fund. The Irish Government’s response to campaign correspondence, whilst procedural, did not represent a rejection of the concept, but rather established a pathway requiring Northern Ireland Executive leadership (Irish Government correspondence, DOT-TM25-11858-2025).

Second, formal recognition of the A2 coastal route and the Strangford crossing within the Regional Strategic Transport Network and the emerging Eastern Transport Plan 2035. Without strategic network designation, the project remains trapped in a local transport category that prevents access to strategic funding mechanisms.

Third, meaningful engagement with the May 2027 Northern Ireland Assembly elections, securing specific commitments from candidates across all parties to commission the feasibility work that the Department has repeatedly refused.

Conclusion

Fr Eugene O’Hagan observed that any sense of privileged status no longer exists, and that this is healthy. The Department for Infrastructure’s privileged position — as both operator of the ferry and arbiter of whether it should be replaced — is neither healthy nor sustainable. It is a relic of institutional self-interest that belongs, like the clericalism Fr Eugene describes, to a different era.

The communities of the Ards Peninsula deserve the same honest assessment of their circumstances that Fr Eugene brings to his Diocese and that the GAA has brought to its clubs. They deserve a Pathway to the Future that is grounded in evidence, not in departmental convenience.

The question is not whether a permanent crossing is needed. The community has answered that question, decisively, at 94%. The question is whether the institutions responsible for serving these communities possess the courage to act.

Kevin Barry BSc(Hons) MRICS Strangford Lough Crossing Campaign www.strangfordloughcrossing.org

References: The Irish News (Fr Eugene O’Hagan article); GAA National Demographics Committee, “No One Shouted Stop — Until Now” (December 2025); Northern Ireland Assembly Hansard, Adjournment Debate: Storm Impact: A20 Portaferry Road (3rd February 2026); Pivotal Public Policy Forum, “Achieving Greater Integration in Northern Ireland: Young People’s Voices” (May 2025); CDC, “Social Connection and Worker Well-being”; DfI correspondence TOF-0128-2025 (9th April 2025); DOF-2024-0440 Annex B; SLC Community Survey (6th November 2024); HITRANS Corran Fixed Link Study; Irish Government correspondence DOT-TM25-11858-2025.