- BY Kevin Barry BSc(Hons) MRICS

- POSTED IN Latest News

- WITH 0 COMMENTS

- PERMALINK

- STANDARD POST TYPE

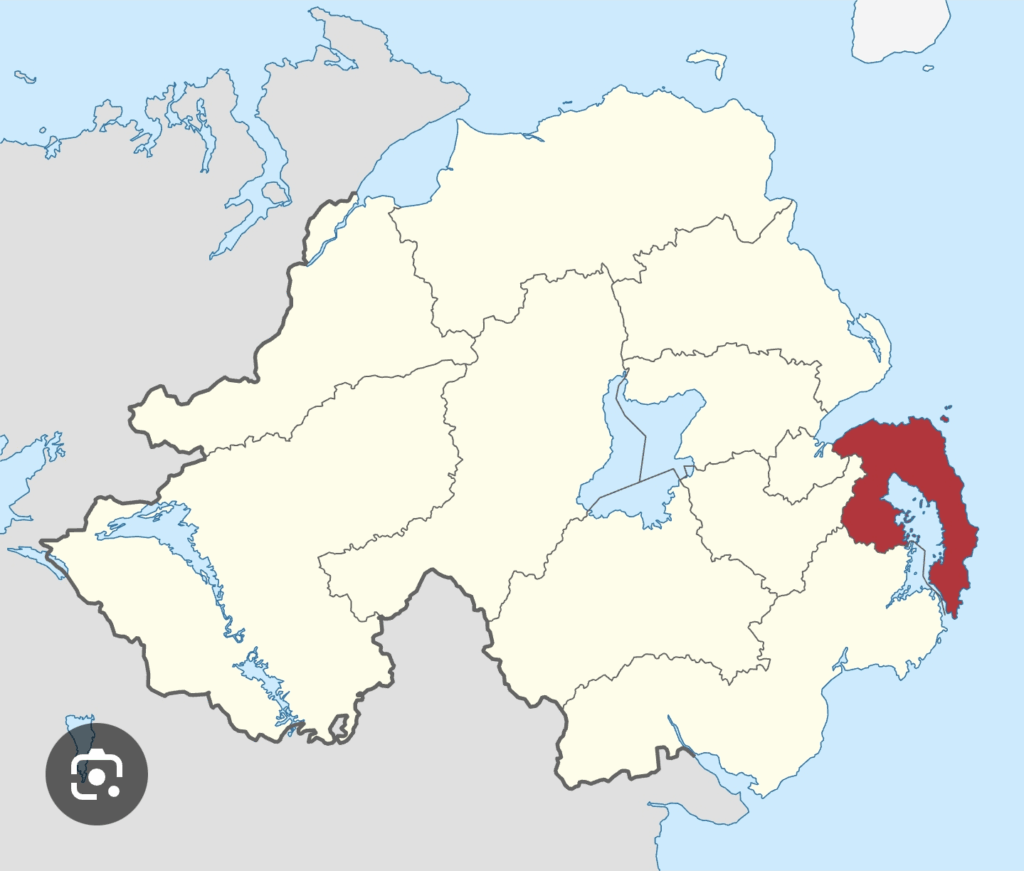

How Strangford “Almost” Got a Bridge

The story reveals a consistent pattern: proposals gained momentum due to genuine transport needs and local campaigning, but were repeatedly blocked by a combination of technical challenges, cost concerns, political opposition, and later, environmental protection.

Historical Timeline of Proposals & Objections

1840s-1875: Early Estate-Driven Proposals

- 1840-1860: Marquis of Downshire toll bridge proposal – £25,000 (roughly £3.5m today)

- Objection: “Impracticable currents”

- 1875: Iron suspension bridge – £25,000 (roughly £3.8m today)

- Objection: “Unsafe foundations” per Board of Works

1920s-1930s: Post-WWI Government Plans

- 1928: Steel arch bridge (8-span, 1,200 ft) – £150,000 (roughly £11.5m today)

- Objection: Cost; ferry deemed “sufficient”

- 1938: Cantilever bridge with detailed blueprints – Cost unclear

- Objection: WWII priorities and “tidal scour risks”

1959: The Barrage Scheme – Most Ambitious Attempt

- Proposal: Barrage (dam) with locks, not a traditional bridge – £400,000 (roughly £11.2m today)

- Would create 5,000 acres of reclaimed land

- Included plans for atomic power plant and airport

- Dismissed traditional bridge as “too expensive”

- Key Objector: Brian Faulkner (Government Chief Whip, later Minister of Home Affairs)

- Initially expressed private reservations in July 1959

- Went public in August 1959 citing excessive cost and tourism damage

- Represented 2,500 petitioners

1960s-1970s: UNESCO Era

- 1969: Suspension bridge proposal – £15 million (roughly £300m today)

- Objection: Environmental impact on newly emerging conservation areas

- 1976: High-level cable-stayed bridge – Cost unclear

- Objection: £8 million needed for approach roads alone (roughly £60m today)

1980s-1990s: Environmental Protection Dominates

- 1987: Immersed tube tunnel (bridge alternative) – Cost unclear

- Objection: Rejected by EU due to Special Protection Area status

- Strangford Lough became UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1986

- 1995-2000: High-level bridge with Lottery funding – £50 million (roughly £105m today)

- Objection: 1998 rejection citing “heritage disruption”

2013-2024: Modern Cost Escalation

- 2013: Strategic Review estimate – £300 million (£400m today)

- Conclusion: “Not economically viable”

- 2024: Latest DfI estimate – £650 million

- Based on Narrow Water Bridge extrapolation

- However, documents show this estimate is heavily disputed as methodologically flawed

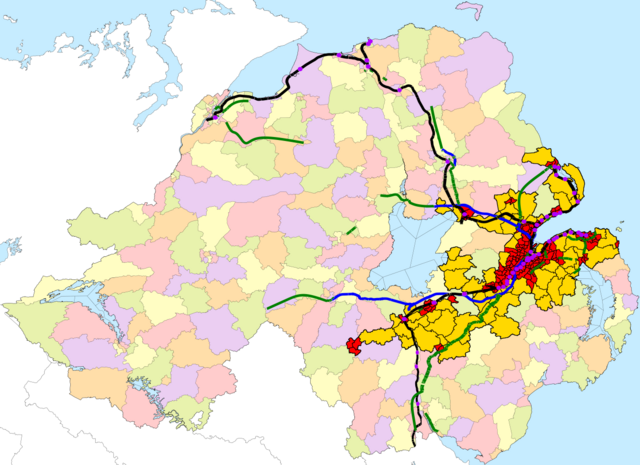

What Has Changed Over Time

Technical understanding: From simple “impracticable currents” (1840s) to detailed knowledge of 60m deep channel, 8-knot tidal velocities, and complex foundation requirements.

Environmental awareness: Pre-1986, environmental concerns were minimal. Post-UNESCO designation, they became a primary blocking factor.

Cost escalation: From £25,000 (1875) to £650m (2024) – far exceeding inflation. The 2024 estimate is particularly contentious.

Political dynamics: Early objections were local landowner-driven. Mid-century saw ministerial vetoes (Faulkner, Brookeborough). Modern objections cite cost-benefit analysis and environmental law.

What Has NOT Changed

The fundamental engineering challenge: Tidal currents (up to 8 knots) and deep water (60m at the narrows) have always been the core technical obstacle.

The “ferry is sufficient” argument: From 1928 to 2024, authorities consistently argue the ferry (operational since 1610) adequately serves the 650 vehicles per day.

Lack of political will: No government has ever committed serious funding to overcome the challenges.

The “almost” factor: Every generation sees renewed local campaigning, keeping the idea alive but never achieving breakthrough.

The Politics – Religion or Class/Geography ?

Based on the historical documents, in terms of religious bias, surprisingly, there is NO direct evidence of anti-Catholic sectarian bias in the Strangford crossing rejections. However, the context reveals important nuances:

What the Evidence Shows:

No Sectarian Motivation Found

1. Geographic/Economic Focus

- Brookeborough’s vetoes (1945-1952) targeted infrastructure across NI, not specifically Catholic areas

- His 7 vetoes affected predominantly Protestant/Unionist areas: Bann Bridge (Portadown), Omagh, Enniskillen, Lisburn

- Primary motivation: “Farmer’s friend” protecting agricultural land, not religious discrimination

2. Strangford-Specific Factors

- Brian Faulkner (1959 opponent):

- County Down native with holiday home on Islandmore island in the lough

- Personal connection to area (protecting tourism/environment)

- Later became pro-reform PM (1974 power-sharing Executive)

- Terence O’Neill (1959 proposer):

- Unionist PM, but modernizing/reformist

- Wanted development, not sectarian blocking

3. The Peninsula Demographics

- Ards Peninsula was (and remains) predominantly Protestant/Unionist

- If sectarian bias existed, you’d expect Protestant areas to GET infrastructure, not be denied it

- Yet Strangford crossing was repeatedly rejected despite serving Protestant-majority area

Broader Stormont-Era Context (Relevant Background)

Undeniable Historical Reality:

- Stormont 1921-1972 had systemic discrimination in housing, employment, voting

- Nationalist/Catholic areas often received less infrastructure investment

- Gerrymandering and resource allocation favored Unionist areas

BUT for Strangford specifically:

- No evidence this was a factor

- The area benefiting (Ards Peninsula) was solidly Unionist

- Rejection opposed by local Unionist politicians/councils

- Approved by some Unionist ministers (O’Neill), blocked by others (Faulkner, Brookeborough)

The Real Pattern: Class/Geography, Not Religion

Brookeborough’s Infrastructure Vetoes:

- Motivation: Agricultural protectionism + fiscal conservatism

- Pattern: Blocked projects threatening farmland or requiring major investment

- Victims: Rural areas regardless of religion (Omagh, Enniskillen, Strangford all affected)

- 135 deaths from delayed road projects across communities

The Irony:

- Brookeborough’s vetoes harmed Unionist rural areas most

- His “farmer’s friend” image prioritized land over lives

- Protestant communities bore the brunt (Portadown, Omagh, Lisburn delays)

2025 Cross-Community Support: The Key Difference

Why This Matters Now:

The current campaign’s strength is precisely that it transcends sectarian divisions:

✅ DUP (Jim Shannon MP) + Sinn Féin (Chris Hazzard MP) = unprecedented ✅ GAA clubs (nationalist) + Unionist communities = shared interest ✅ Republic of Ireland support + UK government pathway ✅ Ards (Protestant majority) + Border counties (nationalist) both benefit

This is the OPPOSITE of historical sectarianism – it’s a model for post-conflict infrastructure cooperation.

Historical Comparison:

| Aspect | 1840-1972 Era | 2025 Campaign |

|---|---|---|

| Political divisions | Unionist vs. Unionist internal conflicts | DUP-SF cross-party unity |

| Sectarian factor | Not evident in Strangford case | Actively transcended |

| Motivation | Agricultural/fiscal conservatism | Climate action + regional balance |

| Opposition | Local elite interests (Faulkner’s property) | Departmental institutional resistance |

| Support base | Limited to Unionist councils | Cross-community, cross-border, cross-party |

The Narrative Advantage

What You Can Say:

- ✅ “185 years of rejections, but never for sectarian reasons”

- ✅ “Unionist politicians blocked infrastructure for Unionist areas – fiscal conservatism, not discrimination”

- ✅ “2025 represents breakthrough: DUP + Sinn Féin united for first time”

- ✅ “Post-conflict infrastructure that builds bridges between communities, not barriers”

What You Cannot Say:

- ❌ “Anti-Catholic bias blocked previous attempts” (no evidence)

- ❌ “Sectarian discrimination” (Peninsula was Unionist-majority area)

The Powerful Reframe:

“For 185 years, Strangford crossing was blocked by:

- Victorian era: Estate interests

- 1920s-1950s: Agricultural protectionism (Brookeborough)

- 1959: Personal property interests (Faulkner’s island)

- 1972: Troubles/political crisis

- 1986-2000: Environmental protection era

- 2013-2024: Departmental cost inflation

But in 2025, for the first time ever:

- DUP and Sinn Féin support it together

- Republic of Ireland willing to co-fund it

- Cross-community GAA clubs and businesses united

- Climate action makes it urgent

- Peace Plus funding available

This isn’t about overcoming sectarianism – it’s about infrastructure finally catching up with the peace process.”

Bottom Line:

No sectarian smoking gun in the historical rejections. The pattern is fiscal conservatism, elite interests, and (later) environmental concerns – none specifically anti-Catholic.

The real story: A crossing that would benefit a predominantly Protestant area was repeatedly blocked by Protestant politicians protecting their own interests (farmland, property values, budgets).

The 2025 advantage: This cross-community consensus makes it immune to sectarian objections and demonstrates post-conflict maturity that didn’t exist in 1840-1972.

The cross-community support is a strength, not to be seen as evidence of overcoming historical sectarianism (which wasn’t the problem with Strangford specifically).

Does It Stand Any Possibility of Success?

The case against (government position):

- 2024 cost estimate of £650m vs. ferry operating costs of £3.52m annually

- Would take 356 years to recoup costs at current usage

- Environmental designations (SAC, ASSI, UNESCO Biosphere)

- Low traffic volume doesn’t justify investment

The case for (emerging criticism):

- Recent FOI documents reveal the £650m estimate may be grossly inflated (8.6 times more expensive per metre than comparable Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Bridge in Ireland, which cost £106m for 887m)

- A realistic estimate based on actual comparable projects would be £106-358m, not £650m

- Could be designated strategic infrastructure in Regional Strategic Transport Network Transport Plan

- Would complete a vital missing link in the Eastern Transport Corridor

Verdict: The proposal stands little chance under current circumstances due to entrenched departmental opposition and environmental constraints. However, if the cost estimate methodology were challenged successfully and political will emerged to designate it as strategic infrastructure rather than a local crossing, the economics could shift dramatically. The project’s recurring nature over 185 years suggests the demand remains genuine, but it would require a fundamental shift in how the project is evaluated and prioritized.