Current Context of Transport Around Strangford Lough

Strangford Lough is a large sea inlet in County Down, Northern Ireland, separating the Ards Peninsula (eastern side, including Portaferry) from the mainland (western side, including Strangford village and connections to Downpatrick). Currently, the only direct crossing is via the Strangford Lough Ferry, a vehicle and passenger ferry operated by the Department for Infrastructure as part of Northern Ireland’s public transport system.

The ferry runs every 30 minutes, takes about 8 minutes to cross the 0.8 km narrows, and can carry up to 260-266 passengers and 27-28 vehicles (including cars, coaches, or small trucks) per vessel.

It operates year-round except Christmas Day and is integrated into the broader public transport network managed by Translink (which handles buses and trains across Northern Ireland).

Public transport in the area primarily relies on Ulsterbus services:

- On the Ards Peninsula side: Routes like the 9/10 from Belfast to Portaferry via Newtownards (journey time ~1.5 hours from Belfast).

- On the mainland side: Routes like the 16e from Downpatrick to Strangford village.

- Crossings typically involve passengers taking the ferry as foot passengers (or in vehicles), with no dedicated scheduled bus services crossing on the ferry itself, though coaches can technically be accommodated. Travelers connecting between sides often combine bus and ferry (e.g., bus to Portaferry, ferry to Strangford, then bus to Downpatrick).

Without the ferry, road travel between Portaferry and Strangford requires a detour around the northern end of the lough (via Newtownards, Comber, and Killyleagh), covering 60-70 km and taking over an hour, compared to the ferry’s short hop.

Public transport in rural areas like this is described as sparse, with limited frequencies and poor signage in some cases.

Proposals for a bridge over the narrows (e.g., a 550m+ structure) have been discussed as a potential replacement for the ferry, though none are currently under construction due to high costs, environmental concerns (the lough is a protected marine area), and funding challenges.

Historical ideas, like a 1959 barrage plan, were abandoned amid opposition.

Hypothetical Impacts of a Bridge on the Public Transport Network

A bridge would fundamentally transform connectivity by enabling uninterrupted road travel across the narrows. Based on current patterns and similar infrastructure projects (e.g., the Narrow Water Bridge over Carlingford Lough, which aims to boost cross-border links),

here are the likely effects on Northern Ireland’s public transport network:

- Reduced Travel Times and Improved Efficiency:

- Direct bus routes could be introduced or extended across the bridge, eliminating the need for ferry transfers. For example, a new or modified route from Downpatrick to Portaferry via Strangford could take 15-20 minutes instead of the current ferry + bus combination (30-45 minutes including wait times).

- Overall journeys from Belfast to southern Ards Peninsula or Lecale (Downpatrick area) could shorten by 30-60 minutes by avoiding detours or ferry schedules. 2 sources This would make public transport more competitive with private cars.

- Enhanced Network Integration and New Services:

- Translink could integrate the bridge into existing routes, such as extending the 16e (Downpatrick-Strangford) eastward to Portaferry and beyond, or linking it with the 9/10 (Belfast-Portaferry) for seamless north-south travel along the peninsula.

- Increased frequencies might be viable due to higher demand from better accessibility. Rural areas around the lough, which currently have limited services (e.g., buses every 4 hours on some routes), could see more options, including express services or connections to the rail network at Belfast or Bangor.

- Better links to tourism sites (e.g., Castle Ward, Mount Stewart) could encourage seasonal or tourist-focused routes, similar to how ferries currently support eco-tourism.

- Reliability and Accessibility Gains:

- Unlike the ferry, which can be disrupted by weather, tides, or maintenance (e.g., reduced capacity during refits), a bridge would offer 24/7 access, reducing delays and improving reliability for commuters, students, and workers.

- Accessibility for disabled passengers or those with mobility needs would improve, as buses could cross without the challenges of boarding a ferry ramp. This aligns with broader efforts to enhance public transport inclusivity.

- Potential Drawbacks and Shifts:

- The ferry service might be reduced or discontinued, as a bridge could render it redundant (similar to how bridges have replaced ferries elsewhere). This could affect foot passengers or those preferring scenic water crossings, potentially requiring alternative provisions.

- Initial disruptions during construction could strain existing bus routes, and higher traffic volumes might lead to congestion if not managed.

- Environmental protections for the lough (a Special Area of Conservation) could limit bridge design, indirectly affecting how public transport adapts (e.g., no heavy rail extension).

- Broader Economic and Usage Impacts:

- Improved connectivity could boost ridership by facilitating easier access to jobs, education, and services between the Ards and North Down Borough and the Down District. This might lead to network expansions, such as better integration with electric vehicle charging or cycling paths on the bridge.

- Drawing from the Narrow Water Bridge example, it could stimulate tourism and cross-regional travel, increasing demand for public transport and justifying investments in greener buses or apps for real-time tracking.

In summary, a bridge would likely modernize and expand the public transport network by bridging a key gap, making it faster, more reliable, and integrated. However, realizing these benefits would depend on Translink’s adaptations, funding, and addressing environmental hurdles.

Alignment with Climate Goals

Northern Ireland’s climate goals, as outlined in the Climate Change Act (Northern Ireland) 2022, target net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, with an interim reduction of at least 48% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels.

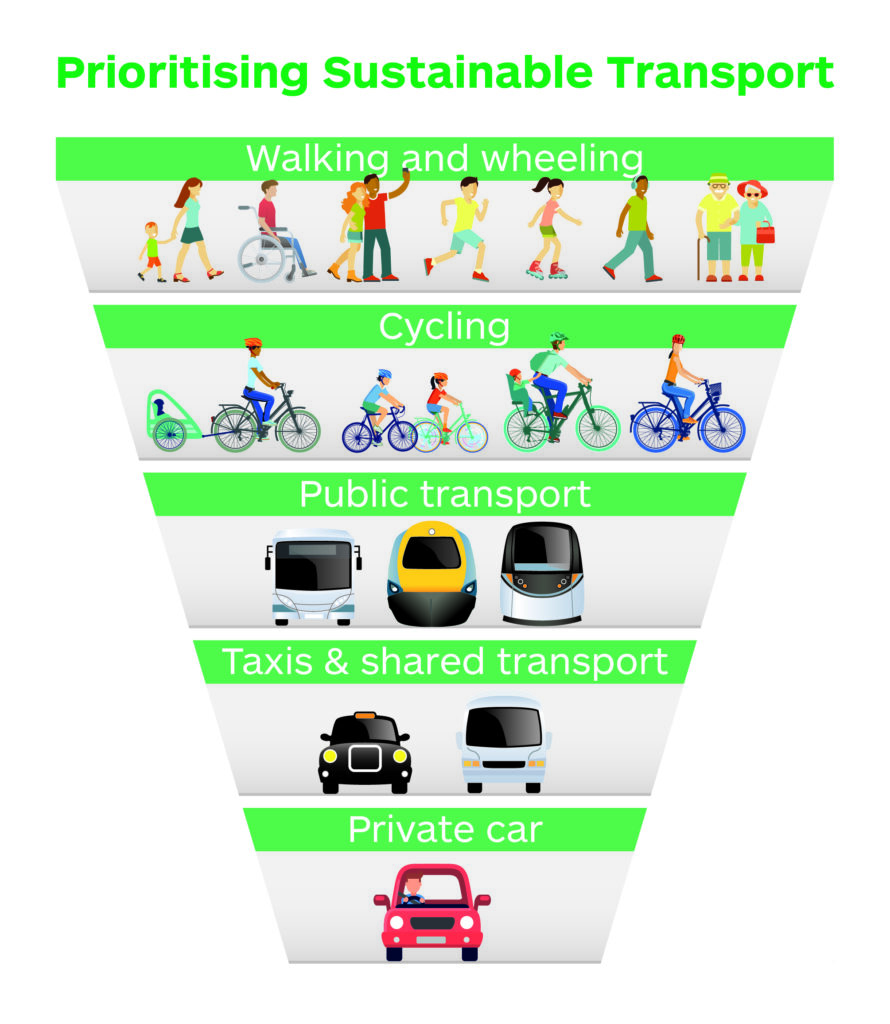

These include decarbonizing transport through a sustainable hierarchy: avoiding unnecessary travel, shifting to low-emission modes like public transport, and improving vehicle efficiency.

Translink, the public transport operator, emphasizes modal shifts to buses and trains, rail electrification, and infrastructure resilience to support these aims.

A bridge over Strangford Lough could contribute positively to these goals in the long term by enhancing public transport efficiency and reducing overall emissions, though short-term construction impacts and environmental trade-offs must be considered.Potential Benefits for Climate Goals

- Emission Reductions from Shorter Routes and Eliminated Ferry Operations: The bridge would eliminate the need for a 60-75 km detour around the lough for road users, significantly cutting fuel consumption and CO₂ emissions for both private vehicles and buses. Current ferry operations contribute to emissions through diesel use and vehicle idling in queues (estimated at 6-12 tonnes of CO₂ annually from idling alone). Proposals suggest integrating renewable energy generation (e.g., solar or wind) into the bridge structure, further offsetting energy use and aligning with net-zero targets.

- Promotion of Sustainable Public Transport: By enabling seamless bus routes across the narrows, the bridge could increase ridership through faster, more reliable services, encouraging a shift from private cars to low-emission public options. This supports Translink’s strategies for modal shifts and could reduce per-passenger emissions, as buses are more efficient than individual vehicles.

For example, extended routes from Belfast to Downpatrick via the bridge could shorten journeys by 30-60 minutes, making public transport more appealing and reducing car dependency in rural areas.

- Long-Term Resilience and Efficiency: Unlike the weather-dependent ferry, a bridge offers 24/7 access, improving transport reliability amid climate change impacts like rising sea levels and storms affecting coastal roads. This aligns with broader infrastructure adaptation efforts, such as those for climate-resilient bridges. Examples from similar projects, like the Interstate Bridge replacement in the US, show that new bridges can incorporate climate-friendly designs to mitigate ecosystem impacts while reducing long-term emissions.

Potential Drawbacks and Challenges

- Construction Emissions and Environmental Impacts: Building the bridge could generate significant one-off CO₂ emissions (e.g., around 190,000 tonnes based on comparable models), plus habitat disruption in Strangford Lough, a designated Special Area of Conservation and Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. This includes risks to marine biodiversity, which contributes to climate resilience through carbon sequestration in wetlands and seagrass. Proposals aim to minimize this via advanced designs, but historical plans faced opposition due to these concerns.

- Risk of Increased Traffic: Easier access might boost private vehicle use, potentially raising emissions if not offset by strong public transport incentives. However, integrated active travel lanes (e.g., for cycling) could counter this by promoting zero-emission options.

- Comparison to Alternatives: An electric ferry upgrade could reduce direct emissions without construction impacts but wouldn’t eliminate queue-related pollution or provide the same connectivity benefits. Bridge proponents argue long-term gains outweigh these, similar to other ferry-to-bridge transitions where net environmental benefits emerge over time.

In summary, a well-designed bridge would likely advance Northern Ireland’s climate goals by fostering sustainable transport shifts and cutting operational emissions, provided environmental mitigations are robust and public transport integration is prioritized. This could yield net benefits within 5-10 years post-construction, supporting the Transport Strategy 2035’s focus on cleaner networks.

However, without careful planning, short-term harms could undermine biodiversity and resilience aspects of climate action.