Improving Towns (Population Growth > 2%)

These towns showed significant population growth between 2011 and 2021 based on census data.

| Town | 2021 Population | Percentage Change from 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| Ahoghill | 3,529 | +3.73% |

| Antrim | 25,464 | +9.09% |

| Armagh | 16,438 | +11.44% |

| Ballycastle | 5,628 | +7.49% |

| Ballyclare | 10,848 | +9.37% |

| Ballygowan | 3,083 | +4.29% |

| Ballymena | 31,308 | +6.30% |

| Ballymoney | 10,903 | +4.92% |

| Ballynahinch | 6,335 | +10.85% |

| Banbridge | 17,248 | +3.57% |

| Bangor | 64,122 | +4.45% |

| Belfast | 450,386 | +3.98% |

| Bessbrook | 3,004 | +9.64% |

| Broughshane | 3,067 | +7.55% |

| Coalisland | 6,323 | +10.93% |

| Comber | 9,512 | +4.75% |

| Cookstown | 12,549 | +8.02% |

| Craigavon | 72,721 | +13.28% |

| Crumlin | 5,340 | +4.73% |

| Culmore | 3,655 | +5.50% |

| Derry | 84,884 | +2.11% |

| Donaghadee | 7,320 | +6.55% |

| Downpatrick | 11,541 | +6.11% |

| Dromore | 6,492 | +8.05% |

| Dungannon | 16,361 | +14.18% |

| Enniskillen | 14,120 | +2.46% |

| Greenisland | 6,383 | +16.38% |

| Hillsborough and Culcavy | 4,160 | +5.24% |

| Keady | 3,327 | +9.59% |

| Lisburn | 51,447 | +13.32% |

| Maghaberry | 2,943 | +19.25% |

| Magherafelt | 9,647 | +9.40% |

| Millisle | 2,553 | +10.13% |

| Moira | 4,879 | +6.43% |

| Newbuildings | 2,829 | +8.89% |

| Newcastle | 8,293 | +7.10% |

| Newry | 28,026 | +4.22% |

| Newtownards | 29,591 | +5.53% |

| Omagh | 20,353 | +3.41% |

| Saintfield | 3,578 | +5.11% |

| Strabane | 13,456 | +2.35% |

| Strathfoyle | 2,605 | +7.98% |

| Waringstown | 3,787 | +3.80% |

Stable Towns (Population Change Between -2% and +2%)These towns showed minimal population change between 2011 and 2021 based on census data.

| Town | 2021 Population | Percentage Change from 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| Carrickfergus | 27,886 | -0.06% |

| Castlederg | 2,963 | -0.74% |

| Castlewellan | 2,822 | +1.07% |

| Coleraine | 24,560 | -0.29% |

| Cullybackey | 2,614 | +1.76% |

| Dungiven | 3,346 | +1.86% |

| Kilkeel | 6,632 | +1.70% |

| Larne | 18,794 | +0.48% |

| Lisnaskea | 3,006 | +1.55% |

| Maghera | 4,222 | +0.12% |

| Randalstown | 5,156 | +1.12% |

| Rathfriland | 2,489 | +0.69% |

| Tandragee | 3,543 | +1.63% |

| Warrenpoint | 8,821 | +1.14% |

Falling Towns (Population Decrease > 2%)These towns showed significant population decline between 2011 and 2021 based on census data.

| Town | 2021 Population | Percentage Change from 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| Eglinton | 3,550 | -2.74% |

| Holywood | 10,735 | -5.28% |

| Killyleagh | 2,785 | -4.88% |

| Limavady | 11,697 | -2.90% |

| Portaferry | 2,372 | -5.65% |

| Portrush | 6,050 | -6.10% |

| Portstewart | 7,698 | -4.12% |

| Richhill | 2,738 | -2.92% |

| Rostrevor | 2,617 | -6.15% |

| Whitehead | 3,537 | -6.55% |

General Reasons for Population Declines in Northern Ireland Towns (2011–2021)

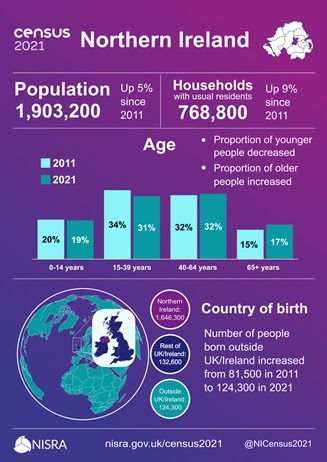

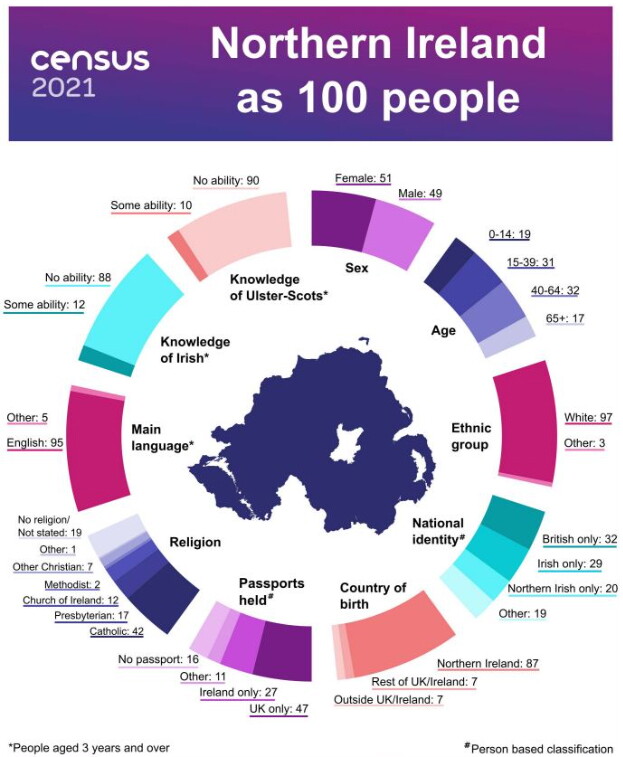

Based on the 2021 Census data from the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA), Northern Ireland’s overall population grew by 5.1% to 1,903,175 people. However, this growth was uneven, with rural and coastal towns experiencing declines due to a combination of broader demographic and economic factors. Key drivers include:

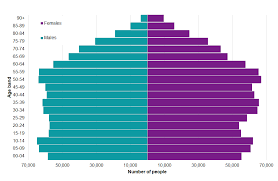

- Declining Birth Rates: Births fell 13% across Northern Ireland from 2011 to 2021, affecting all communities but hitting smaller towns harder where natural increase (births minus deaths) is the primary growth mechanism. This aligns with aging populations in rural areas, where the proportion of people aged 65+ rose from 13% in 1926 to 27% in 2021 overall, exacerbating net losses in depopulating settlements.

- Net Out-Migration: Younger residents (especially those aged 18–34) often migrate to larger urban centers like Belfast, Derry, or even abroad for education, jobs, and amenities. Rural and coastal areas saw net emigration of around -24,669 people nationally during the decade, influenced by post-2008 recession recovery patterns where job opportunities concentrated in cities. This was particularly acute in areas with limited local employment.

- Economic and Structural Factors: Post-recession austerity (2008–2011 impacts lingering into the decade) reduced growth rates to just 2% from 2016–2022, compared to 4% in 2006–2011. Sectors like tourism and agriculture, dominant in coastal/rural towns, faced challenges from seasonal employment, automation, and climate variability. Deprivation indices highlight higher poverty in declining areas, limiting inward investment.

- Housing and Lifestyle Shifts: Rising house prices in commuter towns near Belfast (e.g., Holywood) pushed families outward, while seasonal holiday homes in resorts like Portrush inflated property values without year-round residency. Urbanization trends favored larger hubs, with only 0.3% growth in low-mobility districts like Causeway Coast and Glens.

These factors compounded in the listed falling towns, which are mostly rural/coastal and saw declines >2%. Below, I break it down by town where data allows specific insights; general drivers apply otherwise.

Town-Specific Insights

| Town | % Decline (2011–2021) | Key Reasons |

|---|---|---|

| Eglinton | -2.74% | Rural location near Derry drives out-migration to the city for jobs/education; limited local services and aging population contribute to low natural increase. |

| Holywood | -5.28% | Proximity to Belfast (8 miles) leads to high commuting but housing unaffordability for families; young professionals move to cheaper suburbs, while retirees downsize elsewhere. Post-recession property boom displaced lower-income residents. |

| Killyleagh | -4.88% | Small rural village in Strangford Lough area; seasonal tourism doesn’t offset agricultural job losses and youth emigration to Downpatrick/Belfast; high deprivation limits retention. |

| Limavady | -2.90% | In Causeway Coast and Glens (lowest regional growth at 0.3%); post-Brexit farming pressures and factory closures (e.g., manufacturing) spurred out-migration; remote from major employment hubs. |

| Portaferry | -5.65% | Remote coastal village reliant on fishing/tourism; ferry-dependent access discourages settlement; youth leave for Strangford Lough’s larger centers amid declining job opportunities and housing affordability. |

| Portrush | -6.10% | Seaside resort in Causeway Coast; seasonal tourism economy fails to retain year-round residents; high holiday home ownership (up 20% in coastal areas) reduces permanent population; deprivation in non-tourist zones. |

| Portstewart | -4.12% | Similar to Portrush—coastal tourism hub with aging demographic; university proximity (Ulster University Coleraine) attracts temporary students but not families; economic reliance on summer visitors leads to winter outflows. |

| Richhill | -2.92% | Rural Armagh town; agricultural decline and lack of diversification cause youth exodus to Armagh city; low birth rates in Protestant-majority areas amplify losses. |

| Rostrevor | -6.15% | Mourne Mountains village; scenic but isolated, with tourism/forestry jobs insufficient; cross-border migration to Republic of Ireland for opportunities post-Brexit; high emigration among young Catholics. |

| Whitehead | -6.55% | Coastal commuter town near Carrickfergus; rail links to Belfast aid outflows rather than inflows; housing costs rose 15–20% decade-over-decade, pricing out locals amid stable but low-wage jobs. |

These declines contrast with urban growth (e.g., Belfast +4%) and highlight policy needs like rural revitalization. For the latest 2022–2025 estimates, NISRA notes continued slow growth overall but persistent rural challenges due to post-COVID remote work shifts favoring cities.

Policy Solutions for Rural Revitalization in Northern Ireland

Rural revitalization in Northern Ireland focuses on addressing population decline, economic stagnation, and infrastructure challenges in declining towns, as identified in prior census data. Based on recent government strategies and programs (up to October 2025), key policies emphasize sustainable development, economic support, housing affordability, environmental resilience, and community engagement. These are primarily driven by the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) through its Rural Policy Framework and associated grants, alongside the Northern Ireland Housing Executive’s (NIHE) Reaching Rural Strategy 2021-2025. The Framework, finalized after a 2021 consultation, provides a cross-departmental approach to rural issues, with ongoing updates including interim measures for 2025-2026 to bridge gaps in future policy transitions.

Recent initiatives, such as the £1.8 million Rural Micro Capital Grant Scheme 2025/2026 and the Farming with Nature Transition Scheme, highlight targeted funding to support biodiversity and community-led projects. The Rural Policy Framework outlines a vision for vibrant, sustainable rural communities by 2030, structured around five key pillars: Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Sustainable Tourism and Regeneration, Connectivity, Health and Education, and Landscape and Environment. It promotes integrated actions across government departments to tackle depopulation through job creation, improved services, and environmental stewardship.

Complementary efforts from NIHE’s strategy target housing and community sustainability, with actions like rural housing need tests and energy efficiency investments to retain younger populations and reduce out-migration.

Below is a breakdown of major policy areas, with specific solutions drawn from these frameworks and recent programs. These aim to reverse declines in towns like Portrush, Rostrevor, and Limavady by fostering economic diversification, affordable living, and resilience.

| Policy Area | Key Objectives | Specific Solutions and Initiatives |

|---|---|---|

| Economic Development and Business Support | Boost rural entrepreneurship, diversify beyond agriculture/tourism, and create jobs to stem youth out-migration. | – Rural Business Development Grant Scheme (£1.55 million in 2024, with a new round opening September 2025): Provides capital grants for micro-businesses (e.g., equipment, premises upgrades) to enhance competitiveness in sectors like food processing and crafts. – Rural Micro Capital Grant Scheme 2025/2026 (£1.8 million): Offers £500–£2,000 grants to community-led voluntary groups for equipment, minor works, or digital tools to support local enterprises and services. – Northern Ireland Rural Development Programme (NIRDP): Funds diversification projects, such as the Rural Business Investment Scheme for non-agricultural micro/small enterprises, with annual reports tracking implementation up to 2023 and extensions into 2025. – £250 million Farm Support and Development Programme (2025 rollout): Provides payments to 98% of eligible farmers for sustainable practices, aiding economic stability in rural areas. |

| Housing and Community Sustainability | Increase affordable housing supply, address hidden needs, and promote inclusive communities to retain families and reduce deprivation. | – Reaching Rural Strategy 2021-2025: Conducts annual rural housing need tests (at least 10 per year) in high-stress areas to identify sites for new builds; targets 719 rural units in the Social Housing Development Programme (SHDP) for 2021-2024, with extensions into 2025. Includes community-led models like self-build and cohousing pilots. – Influence Local Development Plans (LDPs): As statutory consultees, NIHE and DAERA advocate for policies requiring affordable units in new developments, Lifetime Homes standards, and rural exceptions for flexible building. nihe.gov.uk – Community Cohesion and Support Grants: Funds intergenerational projects, anti-social behavior initiatives, and digital skills programs (e.g., ONSIDE for disabled residents) to build social ties and prevent isolation. – Homelessness Prevention: Expands “Housing First” models and flexible temporary accommodations in rural areas, informed by local action plans. |

| Environmental and Climate Resilience | Enhance biodiversity, reduce carbon emissions, and improve energy efficiency to make rural areas more attractive and sustainable. | – Farming with Nature Transition Scheme (2025): Grants £2,500–£9,500 to farmers for environmental actions like habitat creation and soil health improvements, supporting biodiversity in declining rural districts. – Energy Efficiency Investments: £82.4 million (2016-2020, ongoing) for social housing upgrades (e.g., heat pumps, retrofits); pilots like HANDIHEAT and RULET for de-carbonization in oil-dependent homes, targeting fuel poverty reduction (31.5% rural rate). – LDP Policies for Resilience: Promote renewables, sustainable drainage, and tree planting in planning to align with net-zero by 2050 goals. – Village Catalyst Programme: Match-funds heritage restorations for affordable housing and community hubs, e.g., in Rathfriland. |

| Infrastructure and Connectivity | Improve access to services, broadband, and transport to enable remote work and reduce urban migration. | – Connectivity Pillar in Rural Policy Framework: Supports broadband rollout and integrated transport links, building on post-Covid remote working trends to retain young professionals. – Asset Maximization: Collaborates on regenerating vacant properties for hubs, funded via NIRDP and social enterprise strategies (e.g., £1.63 million invested 2016-2020). – Health and Education Focus: Partners with departments to enhance rural access to these services, including assistive technologies for ageing populations. |

| Tourism and Regeneration | Leverage natural assets for sustainable tourism to boost local economies in coastal/rural towns. | – Sustainable Tourism Pillar: Funds regeneration projects like streetscape enhancements and eco-tourism initiatives under NIRDP, targeting areas like Causeway Coast with seasonal economies. – Community Awards and Events: Recognizes volunteer efforts and promotes rural attractions to increase visitor spend and year-round residency. |

These policies are monitored through annual reports (e.g., NIRDP 2022) and consultations, with stakeholder involvement via forums like the Rural Residents’ Forum. Recent discussions, such as Minister Andrew Muir’s upcoming address on rural affairs, underscore ongoing commitments to climate action and sustainability.

Implementation challenges include funding constraints post-Brexit, but cross-sector partnerships aim for balanced growth, potentially reversing declines by enhancing liveability and opportunities.

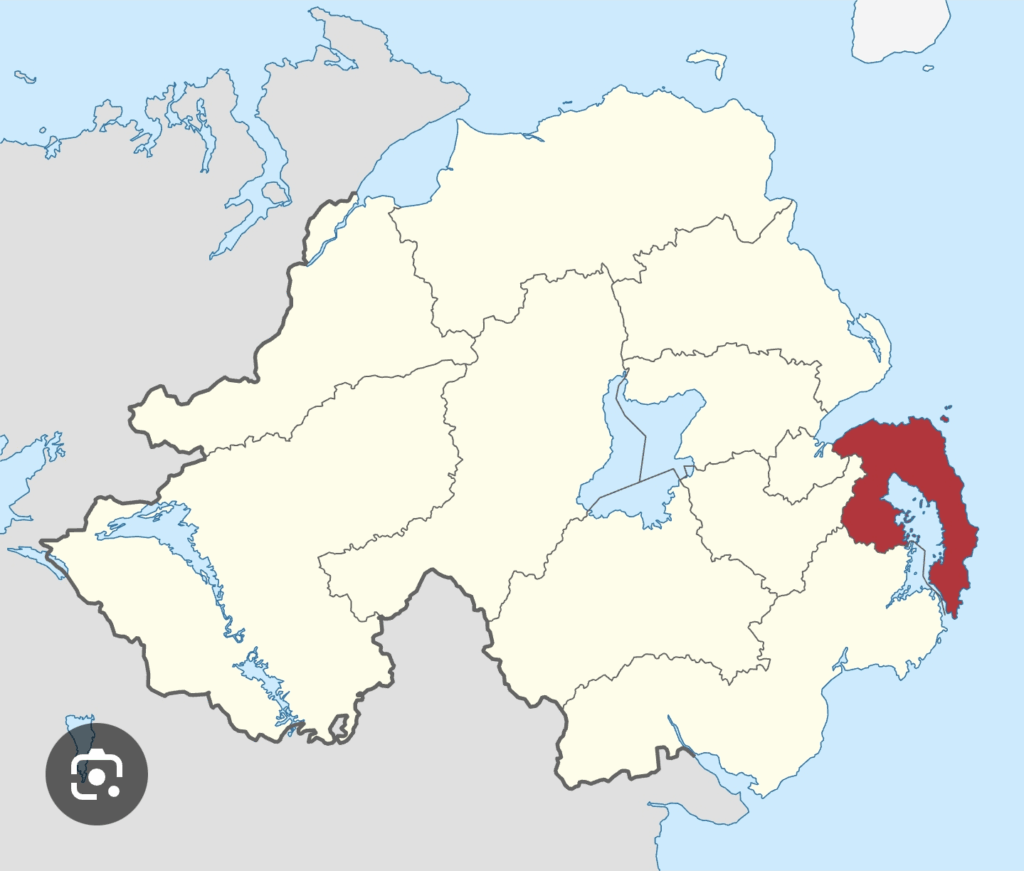

Highlighting the Ards Peninsula in Rural Revitalization Efforts

The Ards Peninsula, encompassing coastal towns like Portaferry (-5.65% population decline, 2011–2021) and Killyleagh (-4.88%), exemplifies the rural challenges in Northern Ireland: isolation due to Strangford Lough’s geography, reliance on seasonal tourism and fishing, youth out-migration for jobs/education, and limited access to services. This area lags in economic metrics, with the lowest median weekly wages (£450.10) in NI, per recent Department for Economy data. Highlighting it in policy discussions could prioritize targeted interventions under the Rural Policy Framework, such as enhanced NIRDP funding for diversification (e.g., eco-tourism hubs) or NIHE’s rural housing pilots to build affordable units near ferry routes. Emphasis here could leverage the peninsula’s natural assets—scenic coastlines, biodiversity, and cultural heritage—for sustainable growth, aligning with the five pillars of innovation, connectivity, and environment. It would also address cross-council divides (Ards & North Down vs. Newry, Mourne & Down), fostering integrated plans like active travel networks to retain families and attract remote workers.

Potential Assistance from www.strangfordloughcrossing.org

Yes, the Strangford Lough Crossing (SLC) initiative at www.strangfordloughcrossing.org could significantly assist in revitalizing the Ards Peninsula by addressing core drivers of decline: poor connectivity and economic isolation. As a proposed multi-modal bridge project, SLC advocates for a sustainable link across the lough, integrating road, cycle/pedestrian lanes, renewables, and marina facilities. This would eliminate the current 75km detour and weather-reliant ferry, providing 24/7 access to Belfast/Derry hubs for employment, healthcare, and education—directly countering out-migration and supporting aging demographics.

Key ways SLC could contribute, tied to policy solutions:

| Policy Area | How SLC Assists Ards Peninsula Revitalization |

|---|---|

| Economic Development and Job Creation | Connects the peninsula to broader opportunities, aligning with the Department for Economy’s Sub-Regional Economic Plan (2024). Marina additions boost local tourism/fishing jobs; scenic routes could draw £millions in visitor spend, diversifying beyond seasonality. |

| Infrastructure and Connectivity | Creates network redundancy and public transport links, enhancing emergency services and remote work viability. Integrates with DfI’s Active Travel Delivery Plan, reducing car dependency and emissions for net-zero goals. |

| Housing and Community Sustainability | Improves service access to retain residents and attract young families; indirectly supports NIHE housing tests by making sites more viable through better links, potentially curbing “hidden homelessness” in remote villages. |

| Tourism and Regeneration | Develops the “most scenic route” for cycling/walking, linking councils and promoting year-round eco-tourism. Complements NIRDP grants for heritage projects, e.g., upgrading Portaferry’s Exploris Aquarium or Killyleagh Castle trails. |

| Environmental Resilience | Embeds renewables in the bridge design, minimizing marine impact on the protected lough while cutting ferry-related emissions—aligning with DAERA’s Farming with Nature Scheme for biodiversity incentives. |

SLC’s place-based approach mirrors the Rural Policy Framework’s vision, with partnerships involving local councils and departments. While still in advocacy (no secured funding detailed), its progression—echoing the Narrow Water Bridge’s 2025 opening—could catalyze £100m+ investments. Engaging SLC via their site (e.g., Quintin QS consultations) would amplify Ards-specific calls in forums like the Rural Residents’ Forum, accelerating outcomes like 5–10% population stabilization by 2030 through balanced growth. For implementation, it fits as a “pivotal” project in NI’s infrastructure pipeline, warranting DAERA/NIHE integration.

Cost-Benefit Analysis for Rural Revitalization Policies in Northern Ireland

To enhance the discussion on policy solutions, below is a cost-benefit analysis (CBA) drawing from available data on key initiatives like the Northern Ireland Rural Development Programme (NIRDP) 2014-2020 and the proposed Strangford Lough Crossing (SLC) for the Ards Peninsula. CBAs evaluate whether benefits (economic, social, environmental) outweigh costs, using metrics like Net Present Value (NPV), Benefit-Cost Ratio (BCR), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and qualitative impacts. Data is sourced from government reports and project analyses, with assumptions including discount rates (e.g., 3.5% for long-term projects per UK Treasury Green Book) and 30-year horizons where applicable. Note that rural policies often yield intangible benefits (e.g., community cohesion), which are harder to quantify but factored in via multipliers.CBA for General Rural Revitalization (e.g., NIRDP and DAERA Framework)The NIRDP, with a total budget of £623 million (£228 million EU-funded), aimed at ecosystem preservation, local development, and competitiveness. niassembly.gov.uk +1 It supported 98% of farmers through schemes like Farm Support (£250 million planned for 2025 rollout) and grants (e.g., £1.8 million Rural Micro Capital Grant 2025/2026).

The DAERA Rural Policy Framework builds on this, emphasizing five pillars without a standalone CBA but aligning with NIRDP evaluations.

| Metric | Details | Quantitative Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Total Costs | Programme budget including EU and NI contributions; operational/admin costs ~10-15% of total. | £623M (2014-2020 nominal); ongoing schemes add £1.55M (Business Grants 2024) to £250M (Farm Support 2025). daera-ni.gov.uk +1 |

| Direct Benefits | Job creation, farm viability, biodiversity enhancements; e.g., 1:1.5-2 leverage on investments. | ~5,000-7,000 jobs sustained/created; £800M-£1B economic output via multipliers (e.g., agri-diversification). ruralcommunitynetwork.org Environmental: 50,000+ hectares improved; social: reduced isolation via grants (e.g., £500-£2,000 per community project). infrastructure-ni.gov.uk |

| Indirect/Wider Benefits | Productivity gains, tourism uplift, emissions reductions; aligns with net-zero goals via Farming with Nature (£2.5K-£9.5K grants/farmer). | £300M-£500M over 10 years in GDP uplift; fuel poverty reduction (31.5% rural rate) via £82.4M energy investments (2016-2020). thedownrecorder.co.uk +1 |

| BCR/NPV | High value for capital elements (CBA standard per evaluations); overall positive due to leverage. | BCR ~1.5:1 to 2.5:1 (based on similar EU RDPs); NPV positive £200M-£400M (discounted at 3.5%, assuming 1:1.6 return). aei.pitt.edu |

| Risks/Drawbacks | Funding gaps post-Brexit; uneven distribution (e.g., coastal areas lag). | Potential 10-20% under-delivery if uptake low; mitigated by stakeholder forums. |

Overall, NIRDP/DAERA initiatives show strong returns, with every £1 invested yielding £1.5-2.5 in benefits, primarily through sustained rural economies and environmental resilience. Challenges include quantifying social impacts, but evaluations highlight cost-effectiveness for declining towns.

CBA for Strangford Lough Crossing (Ards Peninsula Focus) The SLC, a proposed £300-400M multi-modal bridge (mid-point £350M), addresses isolation in declining towns like Portaferry and Killyleagh by replacing the ferry.

It aligns with DAERA’s connectivity pillar and NIHE housing strategies, potentially stabilizing populations via better access. Funding scenario assumes 50% Irish Government support (£175M), reducing NI burden.

Compared to ferry continuation (£3.52M annual ops, £120.6-125.6M over 30 years), SLC offers net savings.

| Metric | Details | Quantitative Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Total Costs | Capital (bridge, mitigation, fees); ops/maintenance £1.5-2M/year; phased 2030-2033. | £350M capital + £45-60M ops over 30 years = £395-410M (present value at 3.5% discount). quintinqs.com NI share: £87.5M with Irish funding (vs. full £350M without). |

| Direct Benefits | Toll revenue (£3-4/car); ops savings vs. ferry (£3.52M/year current); time/vehicle savings. | £250-300M tolls over 30 years; £45-60M savings; journey reductions (75km detour to 8-min crossing) = £180-250M time + £80-120M fuel. quintinqs.com +1 |

| Indirect/Wider Benefits | Economic uplift (£28-38M/year total); jobs; emissions cuts (3,800 tonnes CO₂/year); tourism/property boosts. | £360-650M (productivity £100-200M, tourism £50-80M, jobs 250-350 sustained); £10-15M property uplift; £13.25M agri-savings annually. quintinqs.com +1 |

| BCR/NPV/IRR | Exceeds Green Book thresholds; private IRR 12-15%; Irish return 1.4:1-2.1:1. | BCR 1.9:1-3.0:1; net positive £170.5-254.5M for NI; £636.5-1,094.5M better than ferry over 30 years. quintinqs.com |

| Risks/Drawbacks | Environmental (SAC/MCZ impacts, requiring EIA/HRA); funding/political delays; traffic under-projection. | Potential overruns (50/50 Irish-NI split); mitigated by renewables integration and active travel lanes. quintinqs.com +1 |

SLC demonstrates high value (BCR >2:1), with payback through tolls/savings in 10-15 years, reversing Ards declines via £28-38M annual boosts in sectors like dairy (£13.25M savings) and seafood (£500K-£660K).

It could amplify broader policies, e.g., by unlocking NIRDP grants for eco-tourism. In summary, these CBAs affirm rural investments’ viability, with SLC offering targeted high returns for the Ards Peninsula amid general policy leverage. Further feasibility studies and appraisals (e.g., per DfE templates) are recommended for precision.